- Jake Worthington at Faster Horses Festival: A Preview

- The Faster Horses Festival: A Preview of Michigan’s Premier Country Music Extravaganza

- Ryan Bingham at Extra Innings Festival

- Morgan Wade at Extra Innings Festival, 2024

- Sheryl Crow wows fans at Extra Innings

- Country Music Legend Toby Keith passes at age 62

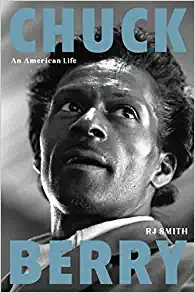

Book Review – Chuck Berry: An American Life

“Chuck Berry: An American Life,” by RJ Smith

Many moons ago, I asked Brian Henneman, the lead singer of the St. Louis area band The Bottle Rockets and one of my musical heroes, about his interactions with Chuck Berry. Brian responded that he had only met Chuck once. He had entered a room in St. Louis while Chuck Berry was screaming at and cursing a photographer with such startling rage that it seemed like physical violence was imminent. Then, Chuck noticed Brian’s presence, warmly reached out his hand, and said, “Hello, I don’t believe we’ve met.” Like many people, Brian Henneman was more discomforted than delighted by being in the presence of Chuck Berry. Chuck enjoyed making people feel uncomfortable. He used his prodigious musical talents and personal charisma in a way to leverage power over those around him. His overarching motivations were control, money, and pussy. He delighted in bullying concert promoters and often displayed contempt for his audience. His sexual obsessions ranged from disgusting to illegal. He was one of the most important figures in 20th Century music.

Chuck Berry is a complicated figure as a subject of a biography. One could simply report that he was a sexual predator and an asshole since there is ample evidence to make those cases. An author could also focus entirely on Berry’s impact on music, celebrating the man who made an entirely new blueprint for popular music, based upon his extraordinary verbal gifts and groundbreaking guitar work. RJ Smith tackles both sides of those equations and much more in telling a story that is significantly more nuanced than my one-dimensional examples would suggest. This is likely the most well-rounded and thorough look the world will ever get of a man who was virtually unknowable. Chuck had no friends he confided to; interviews were verbal chess matches for Berry – sparring sessions that resulted more in deflections or attacks than illumination. One of Berry’s former lovers concluded, “Either he was a very complicated man, or there was no THERE there. I’m still really not sure which.”

RJ Smith had the unenviable task of unpacking a significant portion of our nation’s racial and musical history in this endeavor. There had been crossover black musical artists before rock ‘n’ roll – most notably Louis Jordan and Nat King Cole. However, a significant part of their appeal to white audiences was that both had unthreatening presentations. Jordan built his image on flashy humor, while Cole approached his audience with a calming croon. By contrast, the first generation of black rock ‘n’ roll artists threatened white society by inserting one of their greatest fears, interracial sex, blatantly into the equation. Nothing repulsed or outraged Southern white men more than the thought of a black man sleeping with a white woman. Nothing excited Chuck Berry more than the act of sleeping with a white woman. As we know, in 1955 a fourteen-year-old Emmett Till was murdered in Mississippi for the crime of all flirting with a white woman. Chuck Berry was never going to stop at flirting.

The constraints of racial identity and the ability to create racial breakthroughs are at the core of “An American Life.” The Berry family grew up in a predominantly self-sustaining black community in St. Louis. However, when Chuck saw his God-fearing father, Henry Berry, interact with white people, it was clear that Henry’s survival skill was “knowing his place.” Chuck was nothing if not creative and he seemed to have the sixth sense of when to abide by and when to push against the social norms of his era. He didn’t want to be solely defined by his race, but he also knew that his racial identity was inescapable. If he ever forgot that fact, there were plenty of police officers in the state of Missouri who would give him a fresh reminder. One of the interesting aspects of the book is that Chuck won over local audiences, before he found fame, by acting like a hillbilly simpleton for small, black club performances. It was almost as though he was reversing the blackface tradition.

As one would expect, this biography covers all the key aspects of Chuck Berry’s life – his upbringing, his family, his merger of blues and country music to create something exciting and new, hit records, films, tours, his wide-ranging influence, etc. One of my favorite chapters recalls Berry walking into a mid-1990s gig in St. Louis by the Circle Jerks, a seminal Los Angeles punk band, and requesting to play with them. This is one of the few passages in the book where Chuck seems to be playing more for love than lucre and had to be an unforgettable experience for all the involved parties. (It was also nice to see one of my Facebook friends quoted in this section – Hi, Angela!).

The author also chronicles the darker aspects of Berry’s life – the crime spree that resulted in jail time when Berry was a teenager, the statutory rape conviction that returned Berry to jail in the early 1960s,the infamous tapes of women using a restroom in the late 1980s, and the callousness that frequently occurred after a sexual conquest. RJ Smith details instances where law enforcement used improper methods in addressing Berry’s illegal behavior. However, he doesn’t claim that Berry was innocent either.

One of the larger debates during the social media age is whether it should be morally acceptable to support musicians (dead or alive) who have been involved in ethically or legally unjustifiable acts. Smith somewhat sidesteps this issue, serving more as a reporter than a moralist. He is not constructing arguments to be won or lost. Instead, he is describing the life of a complicated man from all relevant angles and detailing the history that shaped the world of Chuck Berry. He is also reporting on the impact that Chuck Berry had on our history, as well.

As for me, I can love the art while not loving the artist. I’m glad I never had a business dealing (besides attending one lousy show) with Chuck Berry. I will never not love the wit and joy and slices of Americana artfully built into songs like “Johnny B. Goode” and “The Promised Land” and “You Never Can Tell,” among many others. And, I am very glad that RJ Smith penned this excellent biography.

0 comments