- Jake Worthington at Faster Horses Festival: A Preview

- The Faster Horses Festival: A Preview of Michigan’s Premier Country Music Extravaganza

- Ryan Bingham at Extra Innings Festival

- Morgan Wade at Extra Innings Festival, 2024

- Sheryl Crow wows fans at Extra Innings

- Country Music Legend Toby Keith passes at age 62

Music From Big Pink: Myth Debunked, Genius Retained

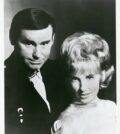

With the recent passing of legendary drummer/vocalist Levon Helm, The Band’s 1968 debut album Music From Big Pink has been enjoying some serious attention on turntables, CD players and iPods. This album is about as mythological as they come in rock history, and many greats such as Eric Clapton and the Beatles have bowed to its genius and credited it with altering their musical course. Along with these accolades, The Band had spent several years playing and writing with Dylan before their first release. This pretty much solidified them as key players in the slow but steady evolution in rock from teenybopper groove to artistic seriousness.

Big Pink did not need years to germinate as a classic; it was immediately embraced as a breath-taking piece of work, an unprecedented gem in the field of popular music. While it met with relatively low sales upon its release, those in the know connected with it out of curiosity about Dylan’s connection with the album. He co-wrote two tunes and also provided “I Shall Be Released.” It was a valuable name-drop for The Band, and those who discovered the album through this portal soon realized that this band was very much into its own thing and certainly not relying on Dylan to sure up its posts.

In the weeks leading up to the announcement of Levon Helm’s advanced illness, I had coincidentally been listening incessantly to Big Pink. As a longtime fan of The Band, I had always gravitated more toward their second self-titled album, sometimes known as the Brown Album. It felt more assured to me, more strident and groove-laden. But with all the mythology surrounding Big Pink, I finally decided to commit to digesting it repeatedly as a unit (even though I had heard all of the songs in other contexts). I played it in the car. I played it at home. I played it exercising. And it became an addictive listen – not for the clichéd ideas of mythology and musical ingenuity that it often inspires in music journalists, but for the album’s very contrived and purposeful effort to make a mark and be different. Much of Big Pink’s mythology is centered around its almost effortless ability to be fresh and unique, yet familiar and timeless. But what many still do not see, even after forty-plus years, is that this image was a result of a concerted effort on behalf of the Band to make this impression on its fans and contemporaries. Too much of the mystical is given credit for the mythological attributes of the Band. However, I argue that this very deliberate attempt at selling an image is mythological in itself – an example of a savvy and artful group who knew exactly what they were doing every step of the way while constructing the myth of their debut album.

Let’s first look at the album art work. On the back of the sleeve we see a picture of a pink house. Those interested in investigating behind the scenes at the time were quick to learn that this pink house, located near Woodstock, New York, was home base to both The Band and Dylan’s musical activities. The basement was set up for rehearsals and demo recording. (In 1975 Columbia Records released The Basement Tapes, a collection of demos recorded in this basement. It was voraciously eaten up by those consumed with the myth of Woodstock and the creative forces that had been emanating from it since Dylan and The Band had moved there in 1966.) Therefore, many listeners assumed that this mysterious album – with nothing on the front cover but a childlike painting by Dylan himself – was indeed recorded in the basement of this house.

Any discerning professional musician’s ear, of course, would immediately refute this erroneous belief. With today’s technology, we can reproduce some seriously professional sounds in our basements. Back in 1968, however, you needed a proper studio to create what we hear on Big Pink: rich, sparkly vocals, proper instrument separation and mixing, lush reverbs, punchy drums, and impeccable silences. There is no way that Big Pink would have carried that punch had it been recorded with Garth Hudson’s 1/4-inch tape recorder (that gave us much of the rough and ready Basement Tapes). In fact, Big Pink was recorded in three world-class studios: A&R in New York, and Capitol and Gold Star in Los Angeles. Signed by Capitol records, The Band had at its disposal as much funds as necessary to capture the essence of its rustic vision. This by no means takes away from its greatness. If anything, the knowledge that this record had as much of a budget as any major label release at the time makes its success as a mythological creation even more impressive. It succeeded by having the means to properly craft a sound that reflected exactly the image they were trying to sell to the public.

When discussing Big Pink as perpetuating an antiquated image, we cannot ignore the photographs by Elliot Landy that fans excitedly surveyed upon The Band’s entrance into the larger musical foray in 1968. Invariably depicted in black and white, The Band dressed in old suits, wore bowlers and fedoras, and had facial hair belying their relatively young age. (None except Garth Hudson was yet thirty years old.) The photographs communicate a casual, laid-back demeanour; it’s almost as if Elliot Landy just showed up one day unannounced and started photographing them as they always appeared in their daily routine. However, Robertson was well aware of the need to sell an unconventional and non-conformist image. Therefore, he purposely hired a photographer who was not at the time well-known (he later became very well known as a result of these photographs). He did not want The Band to look pretty in the typical rock photography sense; conversely, he wanted them to look like they didn’t care. He wanted the audience to look upon The Band as a group of musicians who were intent on creating timeless music with little or no concern for the trappings of fame or success. He wanted The Band to be perceived as being stumbled upon by the world, an accidental discovery that reaped magic in the form of Big Pink. The reality is that the photos were doctored to look that way, just as the album was meticulously crafted by the best in the business to match this image. The fact that this synergetic vision worked holds just as much genius in it as the original mythology itself.

The real magic that sold the mythology of the Big Pink, however, was the performances. When this album was released, the overriding discussions that occurred over turntables and hash pipes were about the incredible dynamic among the members. Listeners marveled at The Band’s tight yet rollicking harmonies, in-the-pocket grooves, and soul-inspired spirit of camaraderie. Music From Big Pink was one of the first albums that sold the myth of “live off the floor” recordings. With people picturing this music being recorded in the basement of that pink house, inevitably the assumption was that the songs were done in minimal takes, with all of them in one room banging it out effortlessly. But The Band was all about creating a great sound, and they were more interested in achieving this by any means possible rather than adhering to unnecessary standards such as everything being a strictly collaborative, live effort in the studio. The important thing here is to not to assume that they were above using the latest studio tricks to achieve their purpose, and this included a lot of vocal and instrumental overdubbing. Who do you think is doing the multiple guitar parts all over the record? They only had one guitarist. This is just conjecture, but Robbie Robertson probably took a few days by himself and just laid down all his parts with no one else around. The idea that that they were all in the same room all the time for the recording of Big Pink is a myth, just like many other aspects of the album and the promotion surrounding it. Levon even had to overdub the snare drum on a lot of the record due to level issues in the mix. In other words, he just sat there by himself hitting the snare over and over with his headphones on. But it was necessary for the overall sound of the record that he do this, so he did it.

My intention by exploring the myths surrounding Music from Big Pink is not all an effort to take away from its magic. Rather, my admiration of the greatness of the album inspired me to study its mythology and peel back the layers to see the remarkable beauty of its reality. This to me is much more satisfying than the ambiguity of the conventional mythology that’s long been attributed to it. More importantly, it reveals the men behind the myth. They were mere mortals intent on creating great music – and succeeding in the music business. And if they tricked the Beatles into going live off the floor for the Let it Be sessions, or inspired Clapton to quit Cream and explore more organic forms or music, then they pulled off the biggest false pretense hoax in the history of rock and roll.

0 comments